By: Shayla Chalifoux (Muskwasis) of St’át’imc Nation, Sekw’el’was community

Tsícwkan úxwal̓ (I went home) for a St’át’imc language immersion class held in Sat̓ (Lillooet). Connecting with the land of some of my ancestors is one way I deepen my understanding of our relationships with plants. These plant relatives have co-evolved with ta tmícwa (the land) and our Ancestors, forming strong reciprocal bonds over time. I learn valuable lessons from my teachers, classmates, and community. Additionally, some teachings come quietly from listening to the land itself. K’alán̓min̓ ta tmícwa (Listen to the land). In what follows, I’ll share some of the lessons and new relationships that have emerged through my time back in St’át’imc Territory.

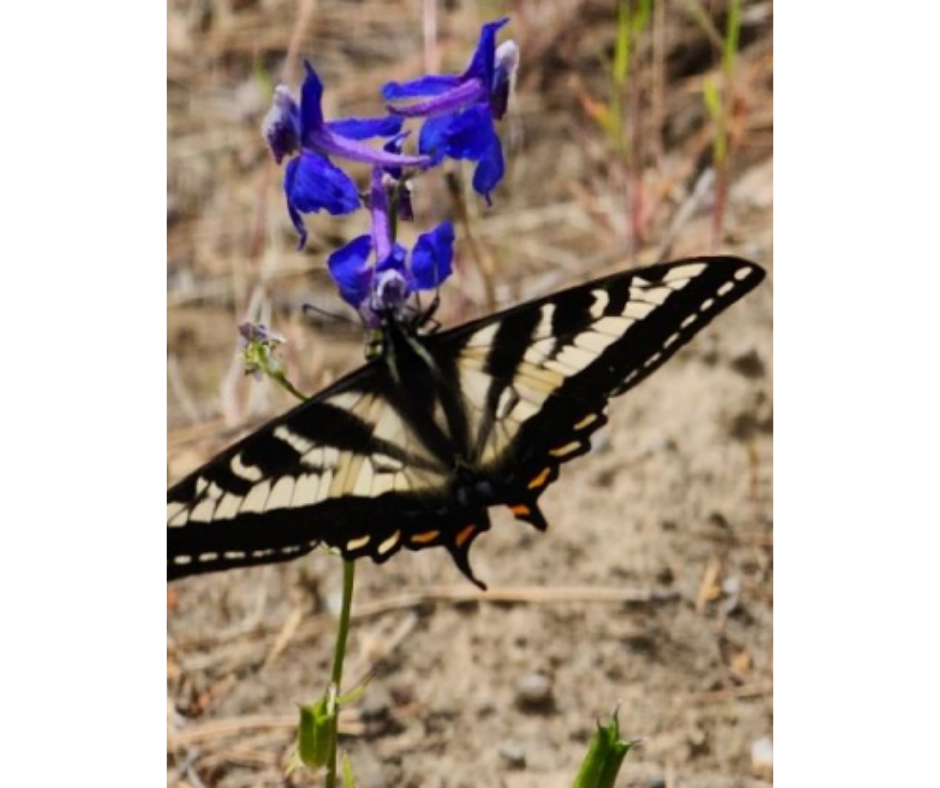

Coming across a native Delphinium, Upland larkspur (Delphinium nuttallianum), part of the Ranunculaceae family, was exciting. This plant relation was spotted on Xwísten, Bridge River tmicw (land). As I spent time with this plant and revelled in the violet and blue flowers, a Pale Swallowtail came to drink their sweet nectar. The relationship between pollinators and plants is just one example of how the natural world is interconnected. Observing these interactions is one way we, as humans, engage with All Our Relations—through our senses. We also connect through the respectful harvesting of plants for food, medicine, ceremony, and material use, continuing reciprocal relationships that have sustained our communities for generations.

Another plant relation I stumbled upon was Sp’ats’en7úl, Dogbane (Apocynum spp.), part of the Apocynaceae family. In my Sťáťimcets (Lillooet language) class, I learned about this plant being harvested and made into twine for fishing nets. Though making the twine was demanding, it was a necessary task because sts̓úqwaz̓ (salmon) is a cultural keystone species for the St’át’imc Nation, central to our way of life (Lyon, Davis, & Bouchard, 2022). Sts̓wan (dried salmon) is beloved to this day while also having a history of being traded for horses and other goods icín̓ as (long ago) (Matthewson, 2005). These relationships between plants, animals, and people illustrate how St’át’imc Peoples were—and continue to be—deeply connected to one another through the land and all that it provides.

Figure 1. Lillooet tmicw, overlooking Seaton lake (Chalifoux, 2025).

Figure 1. Lillooet tmicw, overlooking Seaton lake (Chalifoux, 2025).

Figure 2. Swallowtail drinking from a delphinium on Xwísten tmicw (Chalifoux, 2025).

One final plant relative I want to highlight is Súxwem̓ (Balsamorhiza sagittata), or arrowleaf balsamroot, a member of the Asteraceae family. During my studies in horticultural science, I read extensively about this striking

spring-blooming plant. Súxwem̓ is both meláomen (medicine) and s7ílhen (food), with all parts—from root to fresh shoots—being edible. The root contains inulin, a complex carbohydrate that requires slow cooking to convert into fructose, much like Camassia spp. bulbs. Traditionally, the roots were slow-cooked to make them digestible and t̓ec (tasty). This vibrant perennial has antibacterial and antifungal properties and was utilized in salves, teas, and poultices (MacKinnon, et al., 2014). After learning so much about this plant through books, it was a pleasure to witness them growing in abundance across St’át’imc tmicw—a powerful reminder that ta tmicwa (the land) is our medicine.

All of these relationships guide the way I work with native plants. As I grow my native plant nursery alongside my consulting work, I prioritize culturally significant species to ensure they remain accessible to Indigenous communities. In the face of climate change, we must adapt our growing practices to help plants thrive under shifting conditions—with care, respect, and longterm vision.

My mission is to grow native plants that reflect the diverse needs of Indigenous communities, support All Our Relations, and remain resilient in a changing world. For me, this work is about more than restoration—it’s about remembering, rebuilding, and re-rooting our relationships with the land. Through each plant I grow, I aim to cultivate not just biodiversity, but connection, resilience, and cultural continuity—strengthening the bond between land, people, and culture for generations to come.

Figure 3.Súxwem̓ (baslsamroot) growing on tsal ̓álh (Shalalth) tmicw (Chalifoux, 2025).

References

Chalifoux, S. (2025). Lyon, J., Davis, H., & Bouchard, R. (2022). Wa7 Sqwéqwel’ sSam:St’át’imcets Stories from Sam Mitchell. University of British Columbia.

MacKinnon, A., Kershaw, L., Arnason, J., Owen, P., Karst, A., & Hamersley Chambers, F. (2014). Edible & Medicinal Plants of Canada. Edmonton: Lone Pine Publishing Inc.

Matthewson, L. (2005). When I Was Small – I Wan Kwikws. Vancouver: UBC Press.